Claire Hylton 23

This project started on as an endeavor to create an artistic rendition of Euripides’ Bacchae. I chose this particular tragedy because of the idea of liquidity—the drunken, wine-fueled events of the play, the fluidity of gender, and reality—is at its very center and resonated with the content of the course. I wanted to do more than just digital photography, which is beautiful and essential for many projects, but just didn’t feel right for this one. I wanted to work with my hands and with liquid, and use the idea of liquidity to inform both my images and my photographic process.

My first idea was to shoot black and white 35mm lm and develop it, but it didn’t work out logistically, so I switched gears to thinking about a photographic process that I could do on my own in my dorm room. I settled on cyanotype, which I believe is the perfect medium for this project. It requires simply mixing two chemicals and sensitizing paper with them in a low-light space, for which my dorm room in the middle of the night was perfect. The actual exposure, rather than using an enlarger or other artificial light source, makes use of the sun. The rays of the sun burn the image onto the paper, and the exposed paper is then washed with water until the printed image shows up. It is a very hands-on, inexact science. The images I printed on the paper were digital negatives that I had made previously, and had actually shot on 35mm and subsequently developed. But re-using the images in a different medium and for a different project was strangely perfect for this project. I think of the frantic ecstasy of the women of the Bacchae as revealing another, more archaic and raw self. This is the second life I saw shined into my prints. Together with the light of the sun, and the liquid developer, the water, which is absolutely intrinsic to this photographic process, I felt the capacity for a sort of double life within my own images.

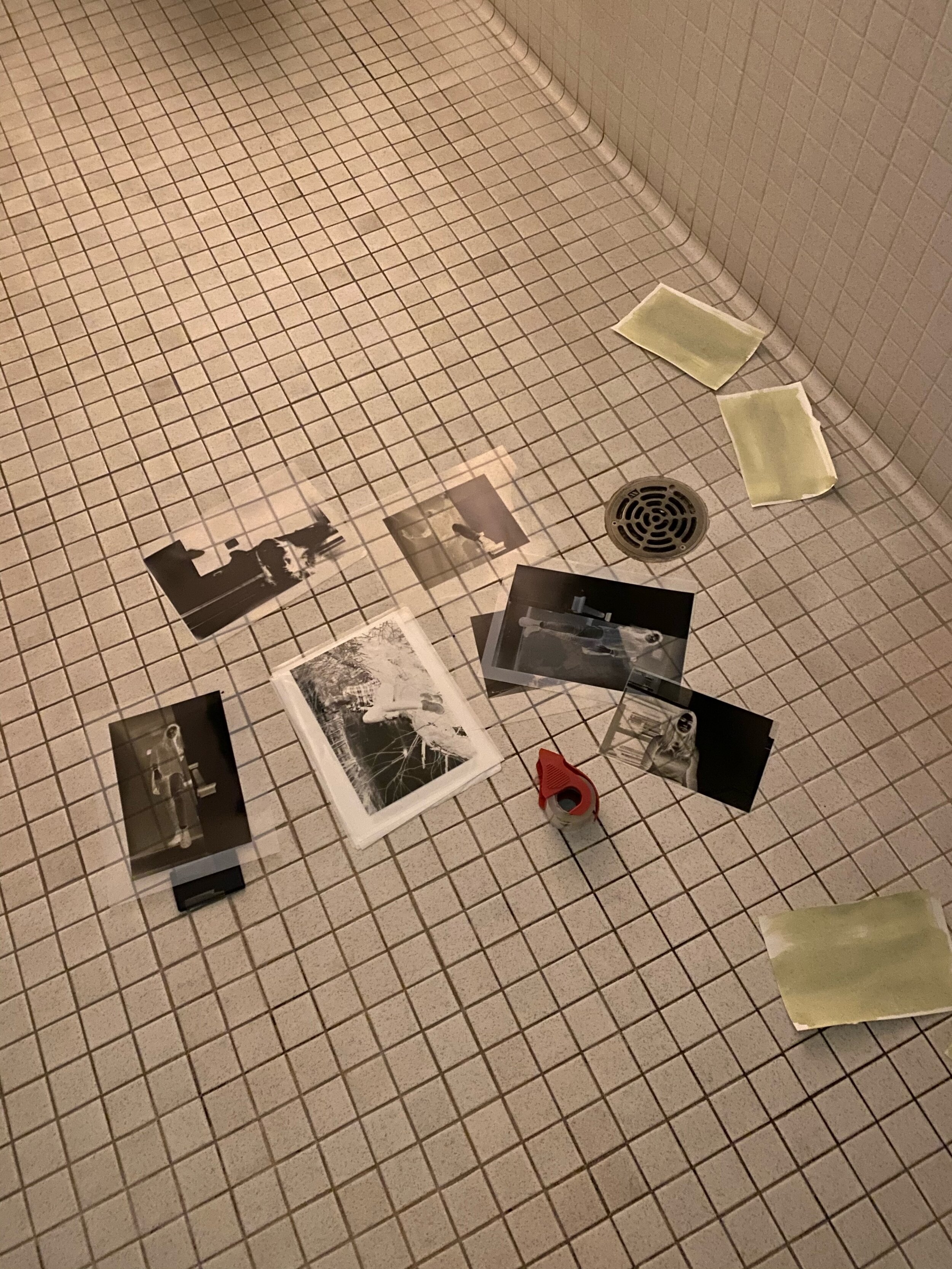

And the process was messy. Water both creates and destroys photography. It’s necessary for developing the prints, but it is the nemesis of the negative. In the pared down, makeshift darkroom I made out of my communal dorm bathroom, water was everywhere. Some of my negatives got water on them, and I was originally disappointed, thinking them ruined. But I realized that the water-stained negatives themselves were an interesting and relevant addition to the portfolio. Liquid as both a creator and destroyer is central to the tragedy that had inspired my project, and it was playing this dual role before my eyes.

I also decided to lean into the idea that had begun to emerge of the duality of liquidity—both creator and destroyer, and the force for exposing another self—in the actual images. On some transparency lm, I drew some images. I re-sensitized the already printed photographs, and re-exposed them. I hoped to make a sort of dual-subject in the photos, and recreate a photographic technique called ghosting, in which the subject of a photograph changes positions during a long exposure, which allows it to be in two places in the same photograph. One of my photos makes use of this technique, and I tried to replicate it in others. I especially was drawn to the idea of re-exposing prints that already had images, because of the line of the Bacchae that led me to this project in the first place. “I seem to see two suns,” Pentheus says as he begins to fall under the trance of Dionysus. I think of cyanotype as a process with two suns—the original exposure of the photograph, and the exposure of the negative to the sun in order to print. This process had me seeing double, working with prints, and then taking photos of the photos in order to share them.

As for the actual presentation, I decided to echo the ghosting technique that I discussed earlier. I took that quite literally with the fabric photograph. The image itself consists of a person, and around it I arranged branches with leaves, hoping to create an abstraction of one of the most iconic classical images, the laurel. The image itself I tried to keep quite simple, and let the natural folds and wrinkles of the fabric show through like ripples in liquid in the blue of the print. I draped it over my sister and the banister at my house, hoping to capture both the transparency and ghostly effect of printing on a sheet of fabric, and also the sort of liquidity of the photograph. I think that looking at the fabric photograph feels like the viewer is looking through water. It spills down and over both her and flows over the banister but there is a roughness to it, which was my attempt to harness both the benevolent and malevolent forces of water. All of my other prints I decided to arrange together in a makeshift collage, in which they can all be seen as their own images, but also taken together in the slightly chaotic amalgamation of faces, plants, and deep blue that was my representation of the emotions I felt when reading the Bacchae in a single viewing moment. The tragedy has a fundamental tension between humans and nature and the divine. I tried to bring out that tension in my photographs by overlaying leaves and branches with human subjects, but ruined by the sun. For one print in particular, I draped it across my own hand when the print was still wet. I loved the idea of the physical malleability of my prints, and wanted to be able to express that in a way that can be seen online, since the ideal viewing experience for analog photography is to see it in person.

I approached this project by hoping to start somewhere meaningful to me—the Bacchae—and end up with a piece that is entirely my own. I believe that this is what I’ve achieved, and this is how I see Pasolini’s tragedy adaptations, too. They begin with the tragedy but take on their own life. Pasolini’s Medea is not the famous tragedy but is instead the creation of Pasolini. He managed to start somewhere meaningful and make his way with it, and create a unique piece of art. I am not an artist, and definitely not one of Pasolini’s calibre. But I believe that this is the point of both classical reception and translation. Not to recreate, but to start somewhere and be led somewhere that is reminiscent of the starting place but something for which the artist/translator can take ownership. I included another folder with photos of my process for this exact reason. Not everything I did was exact, or even what I expected to do when I set out. I hung up shirts and towels over the bathroom lights to create relative darkness; I used my friend’s trash can as a development tank; I got chemicals all over the floor of my room when I was sensitizing my paper. But the process–the way I got from the starting to the ending place–is an essential part of this project and the way I conceptualized it. The final pieces are my art, but so are the messy, raw, unfinished, unplanned images that came out of my creative process.